The Dream Library of Christene Barberich

An impressive book collection of Avedon, Prada, Judd, and Halard adorn The Tiny Apt. founder's home.

In the spirit of choosing joy in these long weeks (see last post), I am thrilled to launch the first entry in our Dream Library series. This section of Hypebooks’ blog features the coffee table book collections of the coolest people out there, whose style, artistic sense, and thoughtfulness I admire. Come here when you find yourself wondering, oh man, how do these cool people find all these cool things? We will tell you (but first subscribe).

I am so honored that the first library we are featuring belongs to

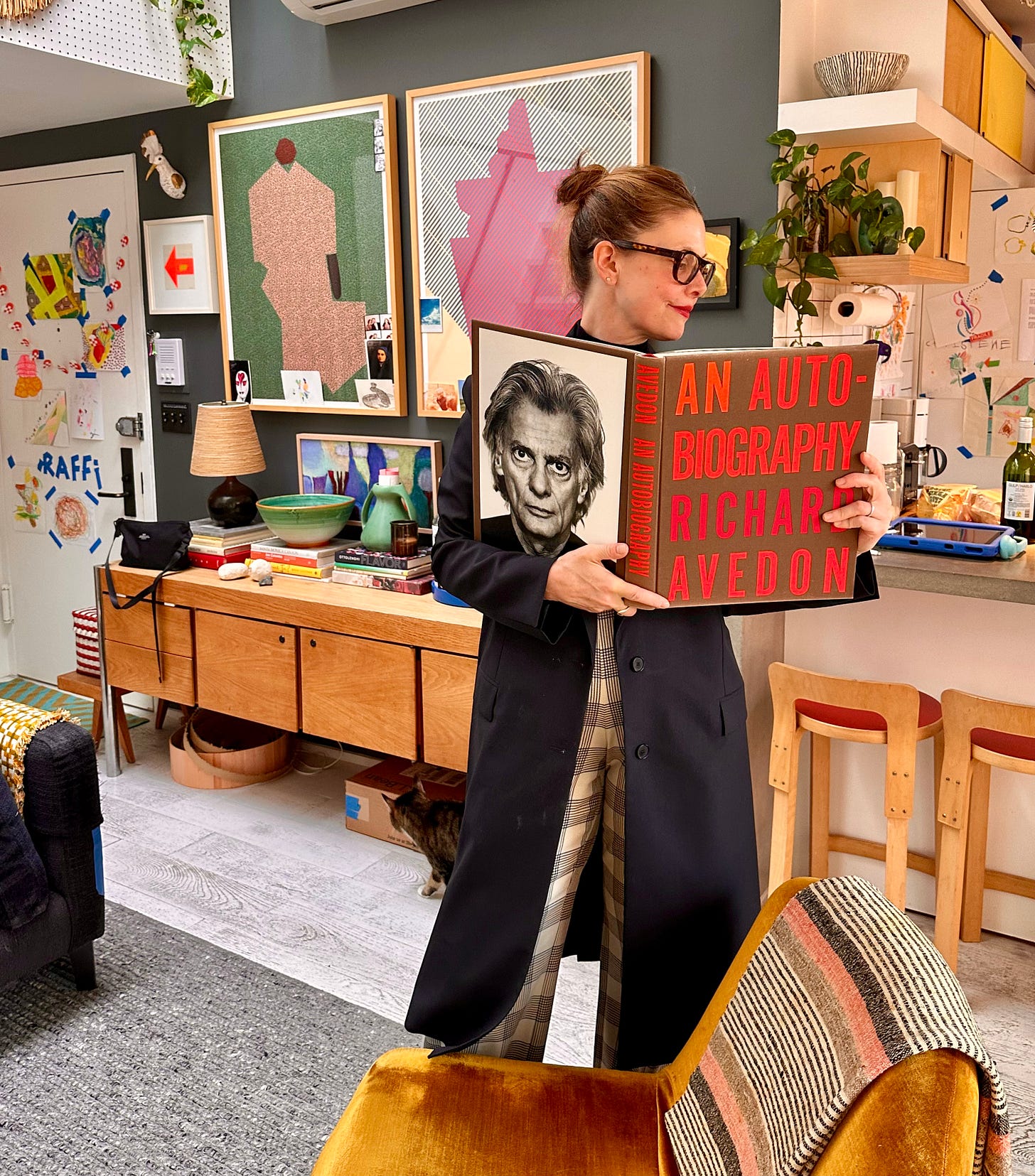

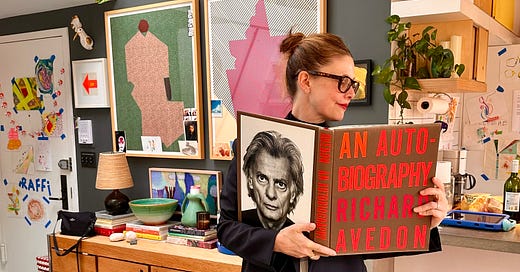

, a true coffee table book connoisseur and founder of , a newsletter about design, fashion, and the discovery of both. It’s a guidebook on honing our collector's eye in pursuit of a new idea of home, canvassing the highs and lows of being creatively courageous. It’s also about how doing so can be its own act of love.I was welcomed to Barberich’s home on a crisp fall Brooklyn afternoon. Before you even enter her apartment, she and her partner’s celebration of curiosity and self-expression becomes apparent in the hallway, which is decorated in dozens of colorful artworks by their five year-old daughter. As we were hanging up our coats, Barberich told me that recently, she has been inviting new work collaborators she hadn’t met in person (e.g., me) to her apartment, in lieu of meeting at a coffee shop. Which immediately made me think of what my grandma used to say, in Hebrew: if there’s room in your heart, there’s room in your home.

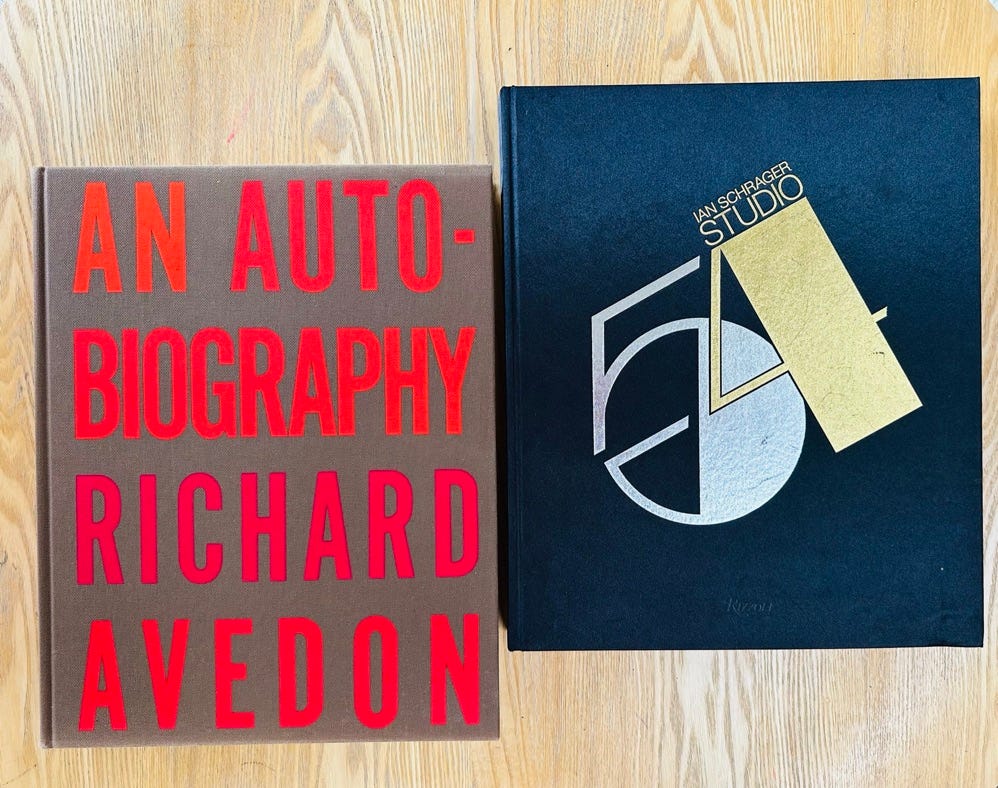

When you walk in, immediately to the left of the front door is a credenza stacked with The Autobiography of Richard Avedon and the candy apple red, leather-bound Pradasphere, the stack crowned by a lamp and a seafoam bowl she found at Brimfield, the famed antiques market. She is a self-described “thrifting maniac” and strikes me as a boutique-heavy, eclectic, and mindful shopper.

As such, most of Barberich’s books were not purchased in a single place, but have been collected from all over. Some come from thrift stores, some from regular book stores, and some from her long, venerated career in the journalistic and literary industries. For instance, when The Autobiography of Richard Avedon was covered by The New Yorker in 1993, where she worked at the time, the historic photographer himself gifted her a signed copy. He asked if she wanted another one for good measure; she did, and gave the second copy to her aunt. As for Pradasphere, published by Prada themselves, the butteriness and richness of the red leather slipcase has a collage of patterns and clothes tipped onto the front. When I asked Barberich about her top creative role models, she was unambiguous. “Obviously Muccia Prada. Definitely. I mean, she's absolutely number one for design of any kind.”

She offered me some tea, and took care not to leave the teabag in too long, else the tea got bitter. I felt a sense of closeness that comes with a shared secret; my British family only ever seems to know that. I figured most Americans simply suffer as they sip, dodging a soggy, stringy teabag splashing in their face.

The Library

Towards the back of her apartment, situated between a floor-to-ceiling window and a white brick fireplace, is Barberich’s library. Flushed with light, the pine built-in shelves carry the weight of a formidable collection of coffee table books, alongside pottery, plants, and fine art (check out her post on how she built it). To start, the shelves showcase her eye for an item’s potential in a thrift shop. Note the portrait of a woman on the top shelf, titled Ava. Standing alone in a thrift shop, the piece could look like an average 19th century portrait of someone that history forgot. In person, in this space, it was beautiful. That Barberich had the foresight to see how this painting could go from looking ancient and nothing more, to being cool in her home, is an example of how developed her thrifting acumen truly is.

As for the books on the shelf: “Coffee table books, to me, are like a luxury,” says Barberich. “It's the kind of accessible luxury that sort of allows us to feel fed, like we have this whole enclave of education and inspiration here at any moment. If I have writer's block, I'll come down and just grab a book and flip through it.”

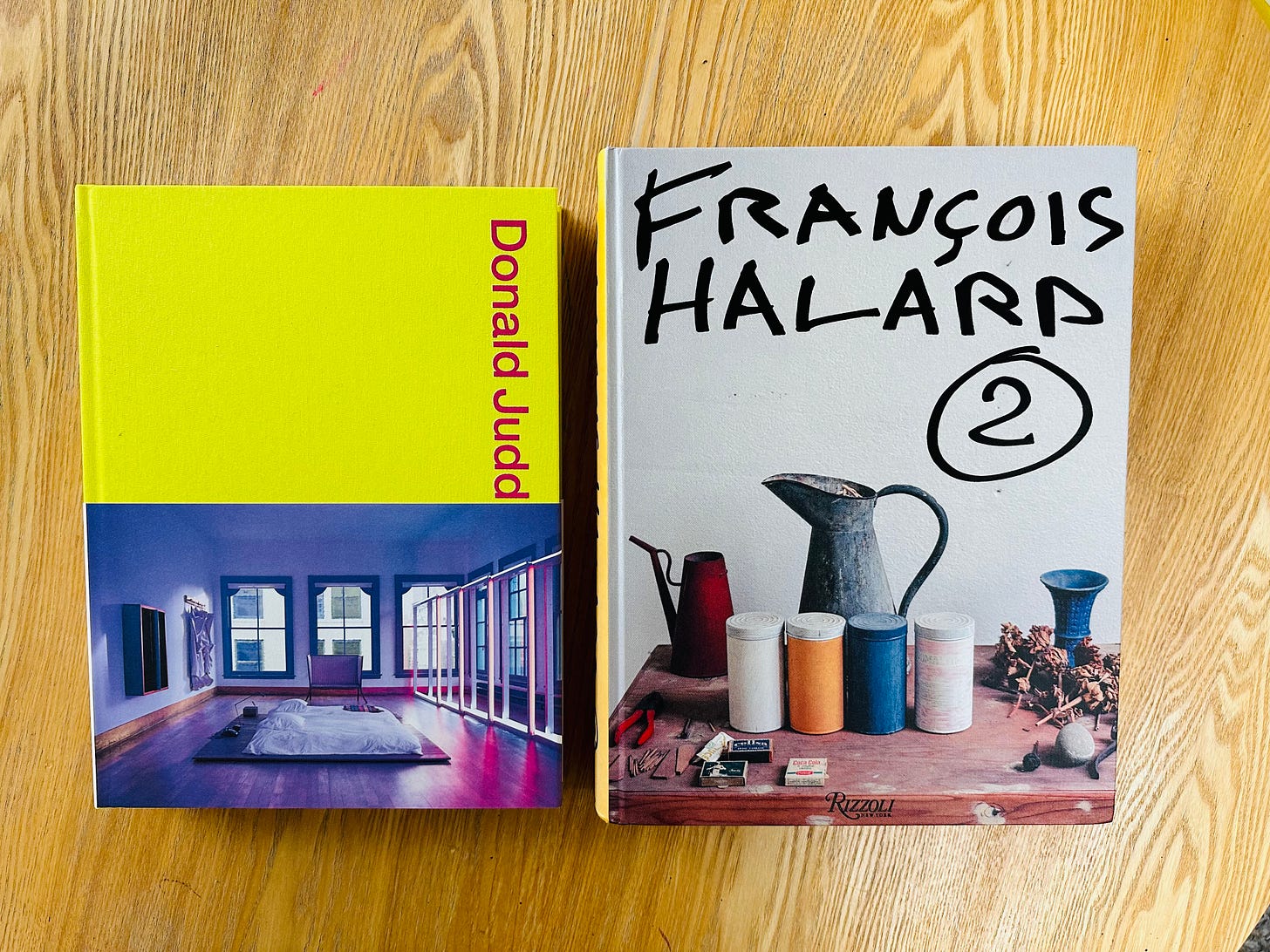

These shelves are where we pulled François Halard 2, Studio 54, Allure, and Donald Judd Spaces, among others, from about fifty or sixty books.

No less than three of her several dozen books were about Diana Vreeland, the former editor of Vogue, a creative visionary who could execute maximalism in the right time and place, and knew how to balance it with simplicity and beauty, a trait which I think Barberich shares. My favorite of the three, Allure, is vintage, published in 1980 (not to be confused with the updated edition published in 2010).

If you read A Tiny Apt, or follow Barberich on Instagram, you may have seen images of the whole space, a masterpiece in a minimalist’s square footage. I wouldn’t quite say she is maximalist, but her home leans that way, tempered by more contemporary modernist aesthetics that channel the urbanism of Phoebe Philo and trim color blocking of Donald Judd (two of her artistic role models, alongside Prada). We pulled the newly-released Donald Judd Spaces from the shelf, his neon monograph about the Judd Foundation buildings in New York and in Marfa, Texas.

Evidence of the mid-century’s worship of stark color and geometric motifs, Judd famously blended his gallery, home office, and living space into one in these buildings. “He integrated the two so seamlessly that it doesn't feel cold,” Barberich admires. He made things “so primitively. And when you make things primitively, it draws your attention back to structure and simplicity. In his case, it feels so decadent to have such simplicity, less ornamentation.”

We also spoke about French interior designer François Halard, whose latest book, François Halard 3, just released last week. Barberich has the second edition, François Halard 2, featuring an ensemble of pottery on the cover. Unlike so many interiors covers, his are unpretentious, just like his designs and Halard himself (I pitched him on publishing his book when I was 22, before I ever actually made a book. He was open and kind to me, and I’ll never forget it). It covers his work and style that is reminiscent of Barberich’s: a home that celebrates life using its mementos, ever-so carefully incorporating them into a thoughtful, intentional and eclectic design. Like Barberich’s home, Halard’s homes are full, but not crowded.

We pulled The Colors of Sies Marjan, a tribute to the now-closed but historic New York-fashion house led by creative director Sander Lak. If you want to brush up on color theory and get to better know the difference between tone, hue, shading and tint, this will assuredly give you more joy than that Adobe online course. The photography makes the light its real subject, which helps your brain to define each fabric’s texture on a flat page, second best to touching the clothes themselves. Together, the texture and color create a rich, overwhelming stimulation on the pages, but in a good way.

As for defining her own style, “I think for me, it’s all about the element of surprise. And experimenting,” Barberich says.

Much of that style draws on vintage pieces, but more deeply, on a certain sense of nostalgia. Her Studio 54 book, one of my personal favorite Rizzoli books, is a testament to that love, with its run of black and white shots of Liza Minelli, David Geffen, Brooke Shields, Pat Cleveland, and Diane von Furstenberg partying at the famed New York club.

“I’m a very sentimental person. There’s a dutifulness I find in rescuing pieces of artisanry, pieces that might have been made with love and curiosity rather than decades of skill,” Barberich shares. “I feel called to do it so other people can find beauty in places like thrift stores or something discarded on the sidewalk. You don't need a lot of money to create these beautiful experiences that allow us to express ourselves, and ultimately find ourselves, too.”

As for defining her own style, “I think for me, it's all about the element of surprise. And experimenting,” Barberich says.

Home as a Healer

One of my favorite things about Barberich’s newsletter is how she regularly acknowledges and vocalizes a gentle gratitude for the things she has in her life, far more often than most people. I’m told that is one of the keys to happiness.

For instance: she found a real sense of peace during early Covid isolation in her small New York apartment. Hot take, I know, but that’s what I mean.

After selling Refinery29 and leaving for good at the end of 2020, like a lot of people, Barberich found her home to be the greatest healer. “I was taking care of my family, cooking more, working through the grief and feelings of leaving the company I spent almost two decades building. Through it all, my tiny apartment was this safe space, a nurturing force that helped me find my footing again,” she recounts. “It wasn't just a place to live, but a space to go underground while this next chapter of my life began to emerge. It made me so grateful. And reminded me how it's not about how much space you have, but how you use it that counts."

She believes that can be true for everyone. “Our homes are these temples for not only sleeping and eating, but for ritualizing our lives, reacquainting ourselves with why we appreciate things, why we cherish them, and why we value something that doesn't necessarily have to be expensive or grand, but can be something so small.

Her books were, and continue to be, part of that experience.

“I have a picture of my daughter from a day where we'll just pull down twenty books, sit on the floor, put music on, and just look at them all,” she says. Sometimes, “she'll ask me questions about pictures she sees. Sometimes they're dark pictures, sometimes they're abstract paintings, and sometimes photography.”

I suspect that those days, like the artwork in the hallway, is Barberich’s practice in creative education, her way of nourishing and celebrating her daughter’s cherubic exploration of her own young, creative mind.

As we left Barberich’s apartment, I told her how it was funny that despite dealing in home accessories, I never worked that hard at designing my own spaces until I got married earlier this year, having moved around so much throughout my twenties. For many young New Yorkers, especially those who live with roommates, it’s only your childhood house that’s your “real” home, so there’s no use in investing too much in an apartment you’ll leave at the end of the summer. Which is how you end up with many books, the most affordable and nimble decoration out there. At least, that’s how I did.

In my new marriage, I told her, I have an earnest desire to “build” a home, whatever that means. For me, it started by decorating our apartment meaningfully, my books becoming jewels in a larger treasure. I think many newlyweds start there. Just like all my old apartments, ours is small and we may not be here long, but for the first time, it feels like home. That feeling, Barberich said, comes because a true home is a manifestation of love. You might like your roommates, but you don’t love your roommates. When you invest in the home you share with your partner or children, even if it’s a tiny apartment, you’re investing in the place where your love takes root.

Beautiful!!! I love to see bookshelves and home decor, just subscribed your newsletter :)

Gorgeous! I love Christene's take on things and this is a beautiful piece. The only thing I'd disagree with is ... loving your housemates! I have deep, deep love for the people I've lived with and created spaces with over the years. And feel very nourished by the types of love that come from outside romantic relationships or traditional family systems.